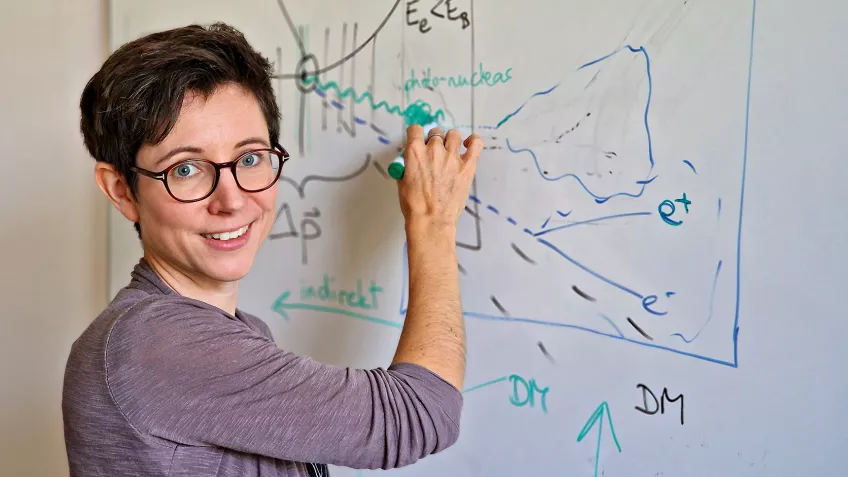

She is standing at her whiteboard in a small office at Fysicum. With the help of her pen, Ruth Pöttgen tries to paint a picture of the invisible. Or rather, a picture of how to measure the existence of the invisible, i.e. the dark matter in space. As a particle physicist, she works with the smallest building blocks of the universe, namely the electrons and quarks that make up the nuclei of atoms.

“It’s amazing that we actually have to understand the smallest particles to appreciate how the whole universe works,” she says.

According to science, there is about five times as much dark matter as visible matter. Dark matter has a mass, meaning it weighs something, and this affects gravity in space. This is how researchers have worked out that dark matter must exist. There is simply too little ordinary matter for the gravitational equations to be correct.

So, is there dark matter in your office right now?

“Yes. However, we can’t know how much at a specific time, but we can calculate an average,” says Ruth Pöttgen.

Is it possible that there is also five times as much of me and my body in the form of dark matter?

“No,” replies Ruth Pöttgen with a smile.

A soup of dark matter

She explains that the interaction between dark matter particles and ordinary matter particles is too weak. This means that the two types of matter hardly interact at all on such a small spatial scale as the particle level. However, they interact via the forces of gravity if we consider existence on a larger scale, on a cosmic level.

Ruth Pöttgen notes that we and our planet are flying through a soup of dark matter particles as our solar system travels through the galaxy. Dark matter is scattered throughout the universe. However, this elusive matter does not have the ability to emit light and become visible to us. Nor does it have a surface against which it could collide; on the contrary, it can pass right through ordinary matter.

The weight of dark matter is unknown

Pöttgen says that there are a large number of experiments being conducted worldwide that are trying to find clues to what dark matter is. Both astronomers and particle physicists are involved.

“We’re trying to find out what kind of particle it is,” she says.

As there are different theories about the nature of dark matter, there is also a need for different kinds of experiments. For example, nobody knows how much a dark matter particle weighs. Some researchers therefore start from the theory that the building blocks of dark matter have a higher mass, within a certain range, while others instead rig experiments that make it possible to look for dark matter particles with lower mass.

Upcoming experiments

Researchers at Lund University have been active in the search for dark matter for many years, including at the international CERN research facility. But now there is also an opportunity to participate in an upcoming and unique experiment, called LDMX, in the US. Nine US universities, along with Lund University, are participating.

“There is no other experiment in the world that can make the same measurements as LDMX,” says Ruth Pöttgen.

Lund University researchers have been given an important role in the collaboration between the universities involved. This includes efforts to extract data from a part of the detector where the electron beam is directed.

“We are responsible for developing and testing electronics and software that can perform simulations and calculations,” says Ruth Pöttgen.

Measuring the effects of dark matter

She explains that the experiment has its uniquely high sensitivity for two reasons. Firstly, it is about the capacity of the electron beam itself. Researchers will try to create dark matter using an electron beam that can shoot off extreme amounts of electrons. At the same time, these particles have to be portioned out just a few at a time. This is because researchers can only work with a handful of electrons at once, but they need to repeat this an immense number of times without running the experiment for decades.

The second reason why LDMX has interesting potential in the search for dark matter is that it will be able to measure changes in both the energy and the momentum of the electrons involved. If the experiment is to succeed in proving the existence of dark matter, it will be via measurements of the energy loss and change in momentum of electrons.

It will not be possible to measure the dark matter itself, but only its effects on the visible electrons. It becomes, somewhat paradoxically, like hunting for the very shadow of the invisible. A challenge that can, however, be realised with the very definite strokes of a pen, on a highly visible whiteboard, in a small office at Fysicum.